The Santol Tree

By Shakira Andrea C. Sison

Originally published in Motherhood Statements (2013)

Mine is a love story that begins in the soft flabby arms of my nanny, Esperanza Dela Cruz. In the Eighties she wore red shorts and told me that if anybody asked, she was always thirty-five years old.

Her nickname was Espie. Once a month she sat me on a low stool to cut my bangs with shears she kept in a rusty pink can labeled Almond Roca. In the kitchen she kept me away from her ampalaya because she said human voices made it bitter. She also told me that if I touched my bellybutton I would die, sleeping with wet hair causes blindness, and that riding bicycles reduces a girl’s chances for marriage.

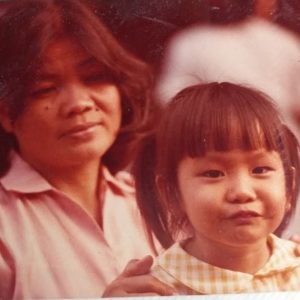

She was a dark, pudgy woman with rounded shoulders like she had been carrying children all her life. There were four of us spaced four years apart, and for three decades she had a monopoly on childcare and affection in my family. I never questioned the fact that I called her Mommy, although now I realize that my own mother must have had some heart hearing me call her that everyday.

The grownups called her Ising, and like the usual sourcing of household helpers, Mommy was recruited from my father’s hometown to help run the family home. Her job included the care of the children of my middle class working parents from 1969 to 1998, beginning in a rundown duplex in the flood zone of Adriatico Street in Malate, to the water-deficient suburb of Parañaque. Of course this devotion doesn’t sound strange to many, I am after all only one in generations raised by outsourced love. But why do I feel like the only one who views this relationship as a little more than professional?

Maybe constant companionship blurs boundaries through time. As the youngest child I had become an appendage to Mommy, or rather she became a right arm to me. Like a filter to all my actions, to me nothing became edible unless it came in a spoon connected to her hand. Baths could not be taken and toilets could not be flushed without her help. Most of all, there would be no sleep until Mommy was ready to put me to bed.

The night time ritual throughout my childhood included my face nuzzled in her arms, a pillow between my legs, and made-up lullabies where I starred under the aliases anak, bunso, and baby ko. In the middle of the night I would wake up to the voice of Johnny Midnight as Mommy had her bottles of water “blessed” by the radio. Very carefully she would decrease the increments of patting until all my senses disappeared, but the moment she stopped touching me I would flinch and she’d resume her rubbing with a furious frequency, hoping I could stay sleeping long enough for her to go back to her radio show. In the mornings she would make me drink the Toning Water made holy by the past evening’s prayers. (In the years that followed it became Mike Velarde’s voice blessing handkerchiefs through the El Shaddai airwaves).

I took advantage of this devotion by once demanding that she feed me at midnight, only for her to find me sleeping when the food was ready. I took a fifty peso bill of hers that she dropped on the bed and claimed it was given to me by The Tooth Fairy. These and other subtle juvenile maneuvers would always result in lectures on manners, truthfulness and propriety, and I took those lessons to heart (especially the reminders not to touch the big mole on her face or to hit her in the chest). She was, after all, my adult role model, even if she could barely read or write. She taught me all I needed to know about life, but more than that, she showed me how it is to truly love.

One evening when I was around ten, I woke up crying from a bad toothache. After trying unsuccessfully to lull me back to sleep, she got up and left the room. An hour or so later, she came back with a warm brown concoction that she asked me to gargle and swish around the tooth in question. It was bitter but I complied, only to find that my toothache had totally disappeared. I went back to sleep, woke up painless the next morning and learned that Mommy had gotten up the previous night with a flashlight in tow to look for the santol tree in our garden. She had cut off a piece of the bark with a kitchen knife and had made a broth from it, and this was what had taken my toothache away.

She showed me the tree and the scar her knife made on the bark. The tree stayed that way for many years, and every time I would see it, I would think of her and her flashlight, exploring in the middle of the night in search of the right tree, cutting the right piece of bark to make the perfect broth to take her baby’s booboo away.

That famed santol tree is now gone. One of the tropical storms ripped it out of the ground many years back. Mommy is gone too. When I left for college my parents slowly found less and less use for an old lady whose taste buds were deteriorating and could no longer cook decent dishes for them. After all, the kids were grown. She was given a severance pay and let go.

She moved back to her barrio into a little hut she called home. It had no running water nor a toilet, but its walls were filled with photos of myself and my siblings. She said when I visited her a couple of years back that she often brags about her “kids” whenever she has guests over, and keeps busy by tending to the backyard crops she sells in town. While on vacation I once found her selling a bag of sitaw in the public market, her arms leathered by sitting out too long in the sun. She said she couldn’t leave until she sold her string beans or else there would be no money for dinner. I gave her the twenty pesos she needed and took her home.

The last time I saw her she hugged me and cried. For the first time I realized how it must have felt when I ran to her dozens of times with a cut or a bruise. She held me tightly and told me how lonely and difficult life was without a family, having no kids of her own. I lied and told her that we are her children and we’ll never let anything happen to her, but we both knew that at the end of that day she would be alone.

I live in New York now. Letters from Mommy take two months to arrive and I feel awful seeing on the stamp how much she spent on postage. The letters are written on candlewax-stained yellow paper and usually begin with her apologizing for her handwriting. Alam mo naman ang Mommy Ising mo, walang pinag-aralan. She continues with a gracious litany of thanks to my parents for being kind to a servant like her, and to me for sending her a monthly allowance. The small amount I send may mean the world to her, but to me it’s like a haircut. The money in the envelope feels like cold heavy shears on my forehead cutting some of the guilt away.

I want to write her back more often but I don’t. Instead I make excuses about my busy life though I am dying to give her details of my small successes in a country she will never know. Whenever I cook I am itching to remind her of our adventures making bibingka in our backyard or how I massaged her shoulder after she hurt it mixing a cauldron of ube halaya all day.

I keep remembering all those afternoons I spent pulling out her gray hairs on the bottom marble step of our stairs. On those hot days in between her chores and the cooking of dinner I would have the rare view of her back towards me. She always told me not to start pulling my grays when I get older. I want to tell her that my grays are all out now, because I want to hear her berate me for being hard-headed and not listening to her advice. I wish she could tell me I was better than that.

In my head I thank her for fanning me to sleep all night during blackouts, for peeling the shrimp, filleting the fish and shelling the crab for all my meals. For cutting the steak into bite-size pieces and never asking for a bite. For showing me that the secret to the kare-kare she made yearly on my birthday was the roasted rice ground by hand with a mortar while sitting on the same low haircut stool in the front yard. I want to say, “I make that perfectly now, Mommy, with my eyes closed. I use a coffee grinder for the roasted rice.” I don’t tell her any of this.

Of course I could write Mommy all these letters of gratitude from thousands of miles away. I did that for a couple of years but after a while the words became cheap, the efforts at expression futile. How many times could I possibly say salamat and mahal kita without having anything to show for it? I love you and I miss you but no, I don’t know when I’m coming home.

It is this same distance that has ironically also blurred other boundaries through time. In letters, emails and text messages to my parents it is so much easier to say the I-love-yous that were impossible in person. Like a lot of parents from their generation, my folks raised us the only way they knew how. It took some time for me to realize that what they lacked in affection and physical presence they made up for by providing everything we needed to succeed: education, discipline and independence. They have been more than successful in this goal. While providing for our immediate physical needs was Mommy’s job and smothering me with love was her passion, raising their children to be strong and productive adults was never a choice for my parents. It was a responsibility.

I have also come to appreciate the hands-free parenting philosophy my parents had and how it has allowed me to flourish as an individual, fight my own battles and discover my own truths instead of having a constant compass or anchor that could have held me back. It made me depend on myself and not wait to be rescued. It has taught me to climb a tree, scrape my knee, scale a wall, and get thrown onto an asphalt road after hitting a kropek vendor on my racer bike. They have allowed me to travel the world, explore my palate, find love, feel loss and hit a tree driving top speed on an Italian moped.

I now have enough understanding of my father’s confidence in destiny and his own children to let them make their own decisions and accept their own failures. I have met enough people whose hands have always been held and who do not hesitate to call their parents for every single need in their adult lives, to know that I find that very disturbing. I now recognize the strength of my mother in letting another woman into her children’s lives to nurture and dote on them the way she couldn’t or didn’t have the chance to. Most of all, I have accepted the courage both my parents had in letting go of our minds and our hearts to seek our own paths, all while making sure our physical needs were attended to and that we got the best education possible. To me it took more than the crossing of fingers to know that if we were equipped with the best tools, we would be okay.

But it will take more than the crossing of a hundred fingers for the old woman who changed the diapers, wiped the sweaty backs, helped with homework, sang lullabies and became my strongest memory of human touch. Mommy’s face is at the end of all hugs I give and receive and she holds the ladles and spoons in every meal I make and eat.

I may have all these rationalizations about my parents but when I think of Mommy’s eyes now opaque from decades of cooking, when I drink a dark tea that reminds me of my childhood toothache or picture her alone in her hut at her age, I still have to face a couple of regrets. One of them is not having the means and the ways to take care of Mommy the way she took care of me. Another is not having a tree in my garden, nor the time to make a broth from its bark, to make all her heartaches go away.

I like to console myself with the hope of one day writing the story of Esperanza Dela Cruz. It will begin with my summer vacation in her barrio when I went against all of my father’s warnings and put a raw oyster in my mouth on a dare. That night, after dancing with Mommy’s nephews to the 80s song The Name Game, I burned up with fever and she cried hysterically for someone to search the barrio for a cure. I remember the smell of kerosene lamps, the sound of prayers and the rough wet washcloth on my forehead and eyes. The water from the thick green-glass Nescafe tumbler was warm and perfect for the orange Biogesic to go down. Her arms were the cure that made the fever do the same.

In this story the song One Way Ticket will play on the AM radio and I will dance to it well enough that Mommy thinks I could join a contest. Mommy will change the station when Imelda Papin goes on because she looks like a “hostess.” In the kitchen I will break an egg trying to grip it with my bare hands like in Ripley’s Believe it or Not. She will tell me that only Lily’s peanut butter works for kare-kare and give me the only compliment I’ll remember from my childhood – that my small hands are perfect for washing the narrow glasses whose bottoms are so hard to reach.

We will make Ls with our fingers and yell “Laban!” as we watch trucks of people on their way to EDSA. Both wearing yellow t-shirts, I will pinch her limbs covered only by a pair of red shorts and say, “Wow, legs!” We will laugh and cheer when June Keithley appears on the black and white television when the revolution is over.

There will be a scene from the 1990 earthquake when Mommy forgot about her own safety as she held still the swinging chandelier in our dining room. At one point she will sit on the four-poster bed and find solace in my mother when her own Nanay died alone on their kitchen floor. It will have the scene in the laundry area where she broke down when I relayed my parents’ message that she was being let go.

Barrio Tumbar will be as I remember it, unpaved dusty roads beside a green river that overflowed every rainy season. Its children will wear hand-me-down clothes from my family and play with our discarded toys. Mommy’s hut will be the same, except that the years of flooding would have created water stain lines on my graduation picture hanging on her wall. In the strongest of storms Mommy will get up on the roof of her completely submerged home and tie herself onto it so she doesn’t join the fate of our santol tree and get blown away. Her roots will be buried deeper and more intricately than that.

My mission is to make a record of it.

I think I can tell the story well enough but I don’t know how to end it. The thought of that woman from my memory is enough to bring me to tears. When I think about her I realize all the work it took raising someone else’s four children for a salary, and how difficult it must have been for my own mother to see me love someone more. I think about how she feasted on my cheeks daily like it gave her the greatest pleasure to love me, and how to this day I still believe that everything I know about love I learned from those arms which longed to hold me day and night – the same arms that would have held on if I didn’t grow up, she didn’t grow old, she wasn’t sent back to the barrio and I didn’t move away. Those one set of appendages I might not ever know again, if life and time and age and the inevitable end this story the only way it will: the childless Esperanza passing on, and my broken, guilty and regretful heart never forgiving myself for not being able to change how the story ends.

(Esperanza Dela Cruz died of natural causes on June 20, 2021. She was 80 years old.)